The Democratic Party is the oldest and only American political party in continuous existence in Indiana since it became a state in 1816. The Indiana and Marion County organizations are, in turn, parts of the national Democratic Party that traces its origins to Thomas Jefferson.

While the donkey is the symbol of the national Democratic Party, the rooster has been historically preferred by Democrats. It originated during the campaign of 1840 when Joseph Chapman, the Democratic candidate for state senator in neighboring , was caricatured as a rooster in a local newspaper cartoon. Generally believed to be trailing his Whig opponent before the cartoon was published, Chapman went on to score an upset victory even though the national Whig ticket was led by the candidacy of adopted Hoosier William Henry Harrison for president. The rooster, variously known as Chapman or Chanticleer, survived as the local party symbol, although it never gained national recognition. The rooster image was used infrequently in the 21st Century, and in 2016 the county party rebranded to a simpler logo in line with the national party.

Jefferson and another early Democratic president, Andrew Jackson, were often recognized at local annual Jefferson-Jackson celebrations across the country, especially dinners, that served as fundraising events and highlighted special guest speakers of national political prominence. Like many party organizations, the Indiana Democratic Party changed the name of its annual gathering, in 2016, adopting the name “Hoosier Hospitality Dinners” in response to the racist legacies of those two presidents. County party organizations, including Marion County, have followed suit, renaming their own events.

Party Structure

The Marion County Democratic Party (MCDP) operates under the rules of the Indiana Democratic Party (IDP), which also is the governing body for county parties throughout the state. All 92 counties are empowered, under these rules, to elect their own officers known as a County Central Committee. The Central Committee consists of a chair, vice chair, secretary, and treasurer, and modern rules require gender balance between the chair and vice chair as well as secretary and treasurer.

In presidential midterm years, precinct committee people (PCs) are elected by Democratic primary voters and serve as representatives of a single precinct. The typical precinct contains nearly 1,600 residents and more than 1,100 registered voters. The chair is empowered to appoint PCs in precincts in which a PC candidate was not on the ballot, or when an elected PC moves out of their precinct. Elected PCs have the ability under Indiana Code to appoint vice precinct committee people (VPCs) within 30 days of their election, after which the chair may appoint VPCs where vacancies occur. The roster of elected and appointed PCs and VPCs are known as the County Committee.

There are 602 precincts in Marion County—meaning that in Marion County, there is the potential for a County Committee of 1,204 individuals, although there are usually far fewer at any given time. The main function of the County Committee is electoral. By state law, PCs and VPCs are responsible for filling elected office vacancies. Elected and appointed members of the County Committee are eligible to vote in these vacancy elections if they represent a precinct within the boundaries of the vacant office.

In addition, larger geographic political jurisdictions exist within Marion County, referred to as wards, which consist of between 8 +and 15 grouped precincts. This contemporary organizational device has a long history. It derives from the 1838 reincorporation of Indianapolis by the Indiana General Assembly that divided the town into six wards, each of which was an election district for town trustee. Traditionally, the role of “ward chair”—a position enabled by state party rules but not required—has served a powerful role in mobilizing PCs, as well as other party duties dictated by the chair, particularly around election time.

Local Democratic Constituency

The location of the state capital made Indianapolis and Marion County an important political center only five years after Indiana achieved statehood. As the new state capital grew, the Marion County Democratic Party benefited at various times from the electoral support of three primary ethnic or racial groups: African Americans, , and .

Germans and Irish, both in religious preference, were major immigrant groups or nationalities in Marion County from the 1830s to the early 20th century. Both groups also voted Democratic. The construction of the canal system in the 1840s and the railroads in the following decades, both of which depended on an immigrant labor base, attracted numerous German and Irish immigrants to the Midwest generally and the growing Indiana capital at Indianapolis specifically. By the middle of the 20th century, more than 3 in 10 Marion County residents claimed German heritage while nearly 2 in 10 cited Irish ancestry.

Black citizens have been another important constituency of the local Democratic Party, especially since the 1930s. The African American population increased greatly after the Civil War. It intensified after World War II, as the Great Depression ended and urban industry became a magnet for Black migration from the rural South. By 2020, the decennial census estimated that slightly more than 28 percent of the population in Marion County was Black.

Of the remaining Democratic population, nearly all of it white Protestant, many derived from the post-Civil War South or from southern Indiana, a region that was particularly sympathetic with the aims of the Confederacy. Known as “,” these southern sympathizers provided a social base for the and its Indiana leader, , after World War I when more than 400,000 Hoosiers became affiliated with that organization. The Klan’s antiforeigner, anti-Semitic, anti-Catholic, and anti-Black agenda briefly gave it the political balance of power in Indiana and Marion County during the early 1920s. It ended as quickly as it began when a Hamilton County jury convicted Stephenson of the 1925 murder of , a young State House worker who lived three blocks from Stephenson in the eastside Indianapolis neighborhood of Irvington. Recent decades have witnessed a shift in political allegiance by many white Democrats to support the Republican party.

Electoral History

Republicans dominated party politics in Indianapolis and Marion County for much of its history. The Whigs, forerunners of the Republicans, elected the first three Indianapolis mayors who served a total of seven years. From the adoption of the city charter of 1847 through 1999, Democrats controlled the office of Indianapolis mayor for only 48 years while Republicans held sway for 98 years.

Democrats enjoyed four periods of dominance in Marion County politics prior to the consolidation of the Marion County and Indianapolis governments in 1969: immediately prior to the Civil War after the Whigs had virtually disintegrated and before the Republicans had supplanted them; between 1885 and the turn of the century when the Irish and the Germans buoyed the Democratic Party; prior to World War I when the Republican Party was split by Theodore Roosevelt’s formation of the Bull Moose Party; and during the four decades that began in the 1920s with the conviction of Klansman Stephenson and the onset of the Great Depression.

Henry Clay Whigs dominated Indianapolis and Marion County during the first half of the 19th century. The disappearance of the Whig party and the rise of the anti-foreigner American party (also known as the Know-Nothings) in its place around 1850-1854 pushed recently arrived German and Irish immigrants into the arms of the Democrats. The rise of the newly formed in the late 1850s, however, placed the Democratic Party in peril, and the antiwar sentiment attached to the Democratic Party during the soon relegated it to its old minority status.

The end of the Civil War saw the beginning of substantial Black migration to Indianapolis and Marion County, and Black voters predictably formed an allegiance to the party of Lincoln. Not until the discrediting of the Ku Klux Klan in the middle 1920s and the economic collapse of 1929 would Black voters shift from bloc-voting Republicans to bloc-voting Democrats.

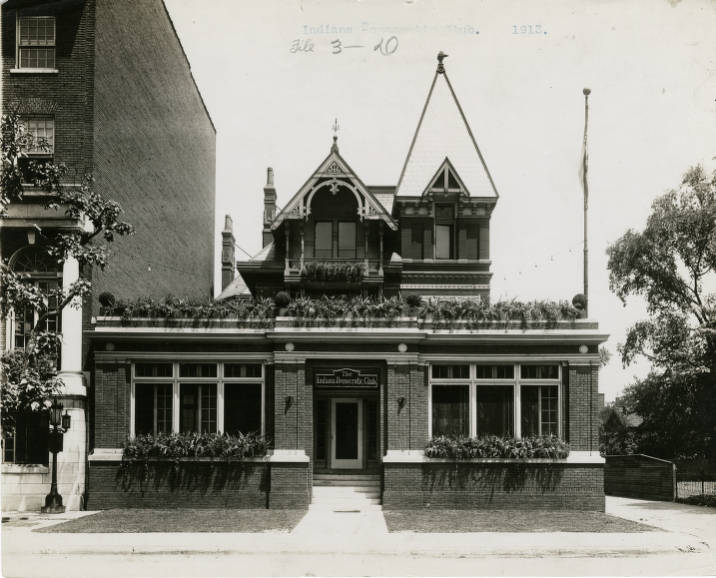

During the Democratic resurgence in the 1880s, the first truly dominant Marion County Democratic politician emerged—. First elected county auditor for eight years (1887-1895), Taggart next served three two-year terms as mayor of Indianapolis beginning in 1895. Later elected chairman of the national Democratic Party, Taggart was the first activist mayor of the capital city, spending the unprecedented sum of $4 million on public works, primarily for and land acquisitions for public parks. Born in Northern Ireland, Taggart’s base support came from recent German and Irish immigrants and their offspring whose lifestyles were threatened by the temperance movement and whose blue-collar livelihoods were threatened by the burgeoning Black community. Taggart’s public life was crowned by his appointment to a vacancy in the U.S. Senate where he served from March to November 1916.

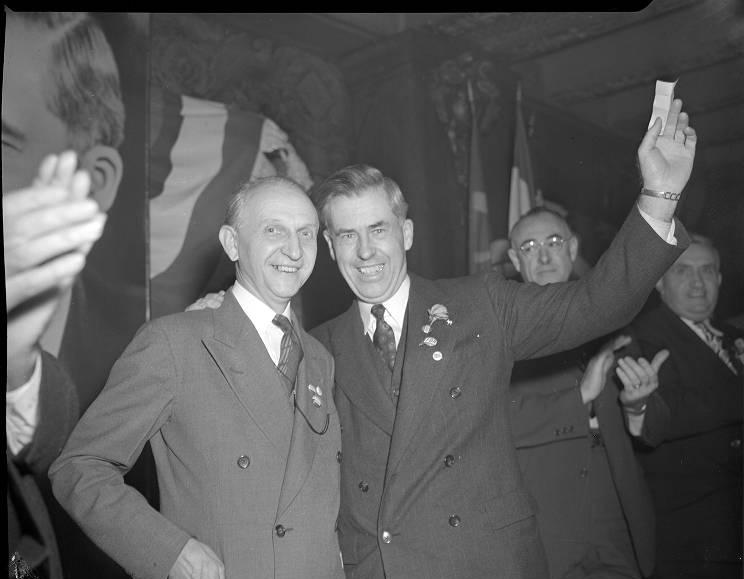

The Marion County Democratic Party was competitive with the normally dominant Republicans until the end of World War I. The Democrats especially prospered after former Republican president Theodore Roosevelt formed the Bull Moose Party and ran for president as its candidate in 1912. The passage of the Volstead Act at the war’s end antagonized the German population, which interpreted as a Republican-inspired punishment for its ethnicity. The rise and fall of the Republican-oriented Ku Klux Klan and its agenda of hate threatened , Catholics, foreigners, and Blacks. The collapse of the economy in 1929—associated with President Herbert Hoover and the Republican Party—confirmed the Marion County Democratic Party as the dominant local political party for a period that lasted almost 40 years.

, a congressman from Marion County, was the first local Democrat since Taggart to achieve almost mythical status. Elected to the United States House of Representatives in every even-numbered year from 1928 through 1942 as well as 1946, Ludlow set a record for longevity among Marion County politicians that was not broken until , son of former congressman , was elected in every general election from 1964 through 1970 and from 1974 through 1992. In 1965, Jacobs Jr. hired a single mother who was working as a secretary at a local labor union. That woman, , would go on to serve 20 years in the United States House of Representatives, from 1997 through 2007, besting her former boss’s record.

The Democratic coalition that provided the base for the careers of Ludlow and Sullivan— African Americans, Catholics, and blue-collar workers —survived well into the 1960s. When was elected mayor in 1967, he was only the third Republican to capture the Indianapolis City Hall in 40 years. By then, two of every five Marion County voters lived outside the Indianapolis city limits. The Republican opportunity for retaining control of Indianapolis city government required the enfranchisement of these suburban voters, most of whom were Republicans.

In early 1969, the state legislature, with an overwhelming Republican majority in each chamber, passed the consolidation statute that established . The legislative mandate to merge Indianapolis and Marion County governments bypassed the popular referendum that characterized all other city-county consolidations in the United States without exception during the 20th century. The Republican governor, whose nomination in the 1968 Republican state convention was dependent on the support of the Marion County Republican delegation, quickly added his signature. later quoted Republican county chairman as saying: “It’s my greatest coup of all time, moving out there and taking in 85,000 Republican voters.”

Indianapolis Democrats, for whom City Hall had provided sanctuary during the worst political times, now faced a franchise expanded to include the overwhelmingly Republican suburbs of Marion County. Broad, countywide, party victories by Democrats in Marion County were unusual, and generally tied to national political dynamics such as the 1974 reaction to the Watergate scandal and the resignation of President Richard Nixon. Lacking favorable countywide demographics, Marion County Democrats focused much of their efforts in the latter half of the 20th Century on elected township offices, particularly in Center Township, as well as statewide and legislative elections.

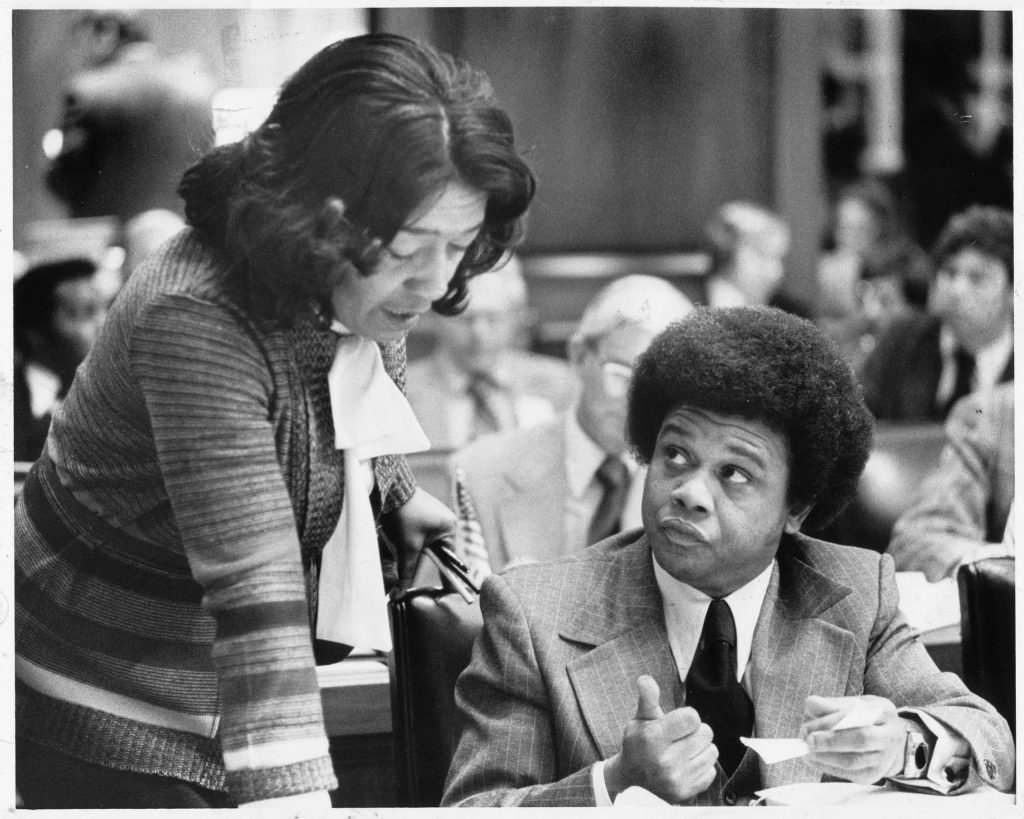

One effect of the political realities flowing from Unigov was the emergence of African American political leadership within the county Democratic Party. These elected and party leaders often broke down barriers in ways that were not politically feasible in other portions of the state. Representative served four decades in the Indiana General Assembly, chairing the influential Ways and Means Committee, and was widely considered one of Indiana’s most influential African American leaders. After 17 years in the Indiana General Assembly, Julia Carson became the first woman and the first African American from Indiana to serve in the United States Congress upon her election in 1996. After two decades of service in Congress, Congresswoman Carson’s political legacy was cemented when her grandson, André Carson, was selected to fill the vacancy created by her death.

Shifting countywide demographics continued to provide Democrats a more competitive electorate, and three decades of unbroken Republican control over the mayor’s office came to an end with election in 1999. That year also saw Democrats for the first time sweep all four at-large seats on the City-County Council, reducing Republican control to a narrow 15-14 majority. Democrats built on this success and in 2002 captured a second countywide office with the election of Sheriff . Riding the coattails of Peterson’s strong reelection effort in 2003, Democrats once again won all four at-large council seats and won a majority on the Council—the first time Democrats had controlled the legislative and executive branches of government since the enactment of Unigov.

For the next decade, countywide elections remained incredibly competitive between Republicans and Democrats, with millions of dollars in campaign contributions flowing into high-profile contests. While Democrats enjoyed many successes, capturing all but one countywide office in 2006, the surprise defeat of Peterson in 2007 brought Republican control back to the City-County Building. This period was characterized by intense partisan battles over issues ranging from tax policy to redistricting, with the Republican-controlled Indiana General Assembly assisting Indianapolis Republicans by eliminating the four at-large Council seats to make Democratic control over the legislative body more difficult.

Indianapolis Democrats enjoyed perhaps their greatest era of success beginning in 2015 with the election of former federal prosecutor as mayor. His victory meant that Democrats controlled every countywide office for the first time and held a majority on the City-County Council. Buoyed by Hogsett’s popularity, and his influence over the party infrastructure, the 2019 election cycle saw Democrats win an unprecedented 20 seats on the Council. Indianapolis Monthly magazine described Hogsett as having “defeated UniGov,” although these victories also highlighted a growing partisan divide between Democratic-controlled Indianapolis and an overwhelmingly Republican-controlled Indiana General Assembly.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.